POST-WAR Britain, a land of austerity, near-bankruptcy and rationing. Football was enjoying a boom in attendances, brylcreem proliferated the dressing rooms and players enjoyed a Woodbine at the final whistle. It was a golden age for the game in terms of the star names that captivated their audience: Matthews, Finney, Lofthouse, Mannion and so on and so forth.

It was also a flourishing time for the amateur game. Crowds were healthy, there were still flickers of the old Corinthian age and the FA Amateur Cup could attract close to 100,000 people to Wembley. When you consider that today, around 150,000 watch the entire Southern League Premier in a season, that is a significant achievement! Against this backdrop, Pegasus Football Club, the last of the great amateur institutions, was established.

A touch of class

For some years, an anti-football movement had been building among Britain’s middle-class. Although the second world war had eroded some of the landed gentry’s confidence and game-cock self-assurance, they looked upon “Association” as the sport of the sweaty, horney-handed sons of the soil. This was highly prevalent among professional folk, notably in the City of London, where “rugger” and “cricket” were the codes of choice.

This was perfectly captured by that grand old FIFA man, Sir Stanley Rous, who commented: “If this can be termed the century of the common man, then soccer, of all sports, is surely his game.”

Some people wanted to recapture the old spirit of the pre-war amateur days, when handshakes were firm and adversaries had a slap-up tea after meeting on the field of play.

Professor Harold Thompson, who later found fame – and some infamy – as the head of the Football Association, was a man of great intellect. Something of a donnish figure at Oxford University, Thompson was renowned as an inspirational teacher who could mix it with quantum physicists and atomic energy scientists alike. He was definitely a man of the new nuclear age.

But Thompson also drew great satisfaction from the old amateur code, the ethos of fair play and “the game for the game’s sake” underpinned by strong Olympian ideals. As professional football became, well, more “professional”, attracting sneers of disapproval from the educated classes, Thompson sought to create a throwback to the classical days of the Corinthians and the Casuals that could also aspire to being something very unique and modern. Uppermost in his mind was a way to remind people that both the working man and people like Oxbridge undergraduates could both enjoy a sport that had acquired, following World War One, a cloth cap and rattle image. Pegasus, a team drawn from Oxford and Cambridge Universities and the brainchild of Thompson, was founded in 1948.

But Thompson also drew great satisfaction from the old amateur code, the ethos of fair play and “the game for the game’s sake” underpinned by strong Olympian ideals. As professional football became, well, more “professional”, attracting sneers of disapproval from the educated classes, Thompson sought to create a throwback to the classical days of the Corinthians and the Casuals that could also aspire to being something very unique and modern. Uppermost in his mind was a way to remind people that both the working man and people like Oxbridge undergraduates could both enjoy a sport that had acquired, following World War One, a cloth cap and rattle image. Pegasus, a team drawn from Oxford and Cambridge Universities and the brainchild of Thompson, was founded in 1948.

Moral compass

It would be prudish to assume that the amateur game in the 1950s was a utopian world of back-slaps and shin-pads. The “brown envelopes in boots” practice was widespread but it wasn’t until the early 1960s, and largely because of a clumsy conversation between the President of Hitchin Town of the Athenian League and a journalist, that the truth hit the media. Sid Stapleton became, in many ways, the “whistle blower” and was exiled for doing it. But back in the early 1950s, many felt that professionalism was damaging football at all levels, let alone the amateurs.

Thompson’s decision to form Pegasus FC provided something of a moral victory for the FA in its battle against “shamateurism”. Although clubs in the Isthmian, Athenian and other similar leagues claimed to be amateur, few could look people in the eye and say that money did not change hands. Pegasus were strictly amateur, drawing their players from undergraduates and those students who were one year away from the universities. There was another important facet to the club, and that was in demonstrating that the public schools and universities still had something to offer football, although they could never be as influential as they were in the developing years of the game.

Pushing and running?

Pegasus firmly adhered to a purist approach to playing the game. This was understandable given their coach at one stage, Bill Nicholson, was a member of the “push and run” Tottenham team that won the Football League in 1951 under Arthur Rowe. Nicholson said some years later that his stint with the varsity teams and Pegasus helped shape his thinking for his managerial career. Vic Buckingham, another progressive coach who may just have had some influence on the development of “Total Football” in the 1970s, also worked with both Oxford and Cambridge Universities and Pegasus.

The influence of Nicholson and Buckingham meant that Pegasus played very fluid, passing football. They were also very fit, no doubt attributable to Bill Nick’s emphasis on physical training. Possibly encouraged by the FA, there was no shortage of current or former professionals willing to assist Pegasus, either with coaching or backroom advice.

Playing the game

This was evident immediately after the club’s first game, a 1-0 win against Arsenal’s reserve side, when the Gunners sent Joe Mercer and Leslie Compton to coach the club. Pegasus played their home games mostly at Iffley Road, the historic ground where Roger Bannister ran the first four-minute mile. But they didn’t play in a league although Thompson pushed for their admittance into the FA Amateur Cup, but on almost preferential terms, allowing them to get the annual Varsity Match out of the way before entering the competition.

In the 1948-49 Amateur Cup, Pegasus reached the last eight, losing the quarter-final at Iffley Road 3-4 to Bromley in front of 12,000 people. Big, curious crowds were commonplace for the club in the competition and in 1951, Pegasus reached Wembley. On the way to meeting one of the pre-eminent names of the amateur game, Bishop Auckland, they beat Slough, Brentwood & Warley, Oxford City and in the semi-final, Hendon in a Selhurst Park replay. In the first meeting, at Highbury, Hendon were within seconds of beating the varsity side and even after Pegasus had equalised in the 86th minute through J.D.P. Tanner (Charterhouse and Brasenose College, Oxford), Hendon had the chance to win through a late penalty. But goalkeeper B.R. Brown (Mexborough G.S and Oriel, Oxford), saved Adams’ kick. The replay was exciting, with Hendon twice leading before J.A. Dutchman (Cockburn H.S. and Kings College, Cambridge), scored two late goals to win the game 3-2. Winger H.A. Pawson (Winchester and Christ Church, Oxford) scored the other Pegasus goal.

The final attracted 100,000 people to Wembley. Auckland were runners-up in 1950 and were Northern League Champions. After a goalless first half, Pegasus went ahead in the 52nd minute through H.J. Potts (Stand G.S. and Keble, Oxford) following a move that was reminiscent of Spurs’ ingenuity at set-pieces. John Tanner, described as the “complete centre forward” in contemporary reports, added a second before Auckland pulled one back in the final minute of the game.

Wembley again

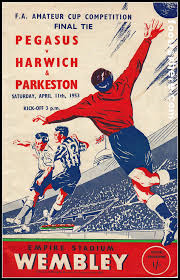

Pegasus’ grip on the FA Amateur Cup was only brief, as they lost in the second round in 1951-52 to another northern giant, Crook Town, before a 10,000 crowd at Iffley Road. But in 1952-53, they were back at Wembley to meet Harwich & Parkeston of the Eastern Counties League.

Hayes, Cockfield, Corinthian Casuals, Slough and Southall were all beaten on route, with the game against the Casuals attracting considerable media attention – the meeting of the two standard bearers of amateurism in its undiluted form. The final again played before a full house at Wembley, but this time, Pegasus easily rolled over the opposition, winning 6-0. Pegasus were too fast for the Essex side and equalled the highest score for the FA Amateur Cup final, thanks to goals from captain D.F. Saunders (Scarborough and Exeter) and J.S. Laybourne (Hookergate G.S. and Emmanuel) aswell as two apiece from R. Sutcliffe (Chadderton G.S. and St.John’s Cambridge) and D.B. Carr (Repton and Worcester).

Influential

Pegasus would never close again to winning the competition and in 1953-54 and 1954-55, they were beaten in the quarter-finals by Brigg Sports and Wycombe Wanderers respectively. But by 1954, Pegasus could also claim to be able to field a full 11 England amateur internationals, including Brown, Ralph Cowan, Tanner, Potts, Pawson and Saunders. The club’s influence had also reinvigorated the annual Oxford v Cambridge game, with Wembley now hosting the meeting of feet as well as minds.

By the early 1960s, however, Pegasus had started to wane. After a handful of poor performances in the FA Amateur Cup, and a decline in the quality of players turning out for the club, they had to weave their way through the qualifying stages. In 1963, they decided to fold.

Had the job been done? In some ways it had, but the amateur game that the club strove to protect was dead 20 years later. But Geoffrey Green of The Times, said Pegasus were one of the most important football teams of the 1950s, comparable to Manchester United and Real Madrid in terms of their influence – that’s some compliment. Today, virtually every club that is called Pegasus – and there’s a lot – owes its name to the duffle-coat wearing undergrads of Oxford and Cambridge.

Like their forerunners, however, the Corinthians and the Casuals, Pegasus ultimately belonged to another age. They wanted to represent the optimistic and hopeful new Elizabethan age, and for a while, they lit up a grey and smoggy Britain. It was grand while it lasted…

Footnote: If Pegasus existed today, they would not be welcomed in the often insular non-league game. Team Bath were the nearest comparison in modern football. They, too, played football with purists ideals, and they, too, were scholars – to some extent. Yet popular opinion about Team Bath was not entirely positive, with many claiming, as they were the team of University of Bath, they were funded by the taxpayer. Such as misconception displayed a lack of understanding of the financial structure of Britain’s universities today. Team Bath did not attract crowds and given their success on the field outstripped the club’s ability to progress up the non-league pyramid, the club stepped down. But Team Bath should have been applauded for their approach to the game, not criticised. While Pegasus were welcomed with open arms and admired, the reaction to Team Bath demonstrated just how society had changed in 50 years.