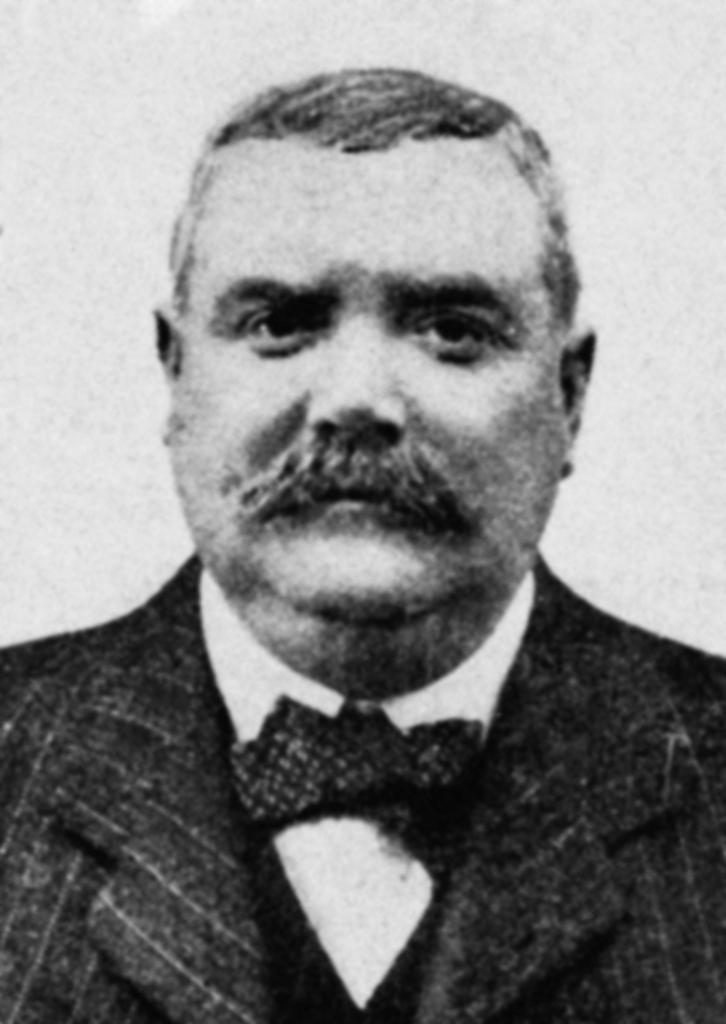

THE role of the football manager didn’t really emerge until the early years of the 20th century and became synonymous with the increased professionalism of the game. The person responsible for the players was generally the secretary and this gradually morphed into a job that included management of the team on the field. It varied a little from club-to-club, but the most important person at the club was essentially the chap that ran it. Tom Watson was one such individual, a stocky, moustachioed individual who could sell anything to anyone and charm the most difficult of characters.

Watson developed the knack of getting the best out of a squad of players. A native of the north-east of England, he was born in April 1859 and was involved with the two Newcastle teams that became United, West End and East End. He was instrumental in Newcastle West End moving to St. James’ Park, but when he moved to East End, his former club went into decline.

Watson moved to Sunderland in 1888 where he began to build a team that was largely drawn from Scotland. Watson, who was just 29 when he arrived at Sunderland, had tapped into the Scottish football scene early in his career with Newcastle and down the years believed that the Scottish player was the finest of them all. The Sunderland team that entered the Football League in 1890 was dominated by Scots and in their second season, they won the first of their league titles. All bar one player had been signed by Watson from clubs north of the border, something of a necessity for Sunderland, whose geographic position meant it was easier to head north to sign footballing talent.

And it was the acquisition of skilled players that defined Watson’s Sunderland – the so-called “team of all the talents”. Sunderland won the Football League in 1891-92, 1892-93 and 1894-95 and were runners up in 1893-94. In their squad they had outstanding players like Ned Doig, Hughie Wilson, John Auld and Jimmy Millar. They dominated English football and were resented by some because they were extremely intolerant of any form of criticism. Watson himself was a very popular and influential figure.

In 1896, Sunderland became a limited liability company with capital of £ 5,000. Watson, who had been attracting the attention of a number of clubs, was lured to Liverpool who were an ambitious outfit who needed a guiding hand to drive them forward. Watson was given a record £ 300 annual salary, which was double his wage at Sunderland, and given the brief to make Liverpool into a footballing power. The Herald, among others, was shocked by his move: “So Tom Watson and Sunderland are divorced! The degree has been pronounced and made absolute and Tom had joined Liverpool. What will the team of all the talents do now, poor things?”.

Despite the disappointment of his departure, the Sunderland public made sure they showed their appreciation of Watson. He was showered with gifts from players, club and supporters of the club. When it was time for him to go, he was accompanied by well-wishers at Sunderland railway station. A large crowd saw him off, presenting him with a silver scarf pin and matchbox.

The journalists liked Watson because he always had time to speak to them and offered interesting sound-bites for their papers. His arrival at Liverpool pushed the club into the spotlight, “this club has, at last, secured a man to take them to the helm”. He was, effectively, Liverpool’s first proper team boss. Watson implemented a rigorous training regime and also had rules about diets and lifestyle. He may have been strict about some aspects of football management, but he also enjoyed having a drink and a sing-song with his players. He was occasionally outspoken and had little time for referees, many of whom he felt were simply incompetent.

In his first season with Liverpool, which was also the first that the club wore red and white, Watson took the club to fifth place. Watson made history at Liverpool in winning two Football League champions in 1901 and 1906, the latter a notable triumph after winning promotion from the second division. Watson was the first manager to win the title with two different clubs. Although his best days were soon to come to an end, Watson remained at Liverpool until May 1915, making him the club’s longest serving manager. He died at the age of 56 after suffering a severe chill while at work. The football world was full of tributes to the man who arguably started the cult of the manager and his record will always speak for itself.